Teen Lands Venture Capital For Accessibility Device

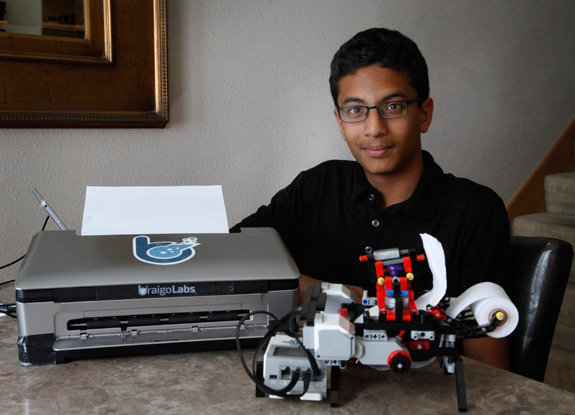

Shubham Banerjee poses with the Braille printer he built out of Legos and a prototype of a Braille printer, left, that he hopes to get manufactured. (Patrick Tehan/Bay Area News Group/MCT)

SANTA CLARA, Calif. — Last December, seventh-grader Shubham Banerjee asked his parents how people who are blind read.

A Silicon Valley tech professional, dad Neil Banerjee told his son to “Google it.”

So Shubham did, and with a few Internet searches he learned about Braille, the tactile writing system used by those who are blind, and Braille printers, which, to the 12-year-old’s shock, cost thousands of dollars. One school science fair victory, a few national accolades, $35,000 of his parents’ savings and a visit to the White House later, Shubham today is the founder of Palo Alto startup Braigo Labs, which aims to become the first purveyor of low-cost, compact Braille printers.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

And last week, Intel Capital, the company’s global investment arm, announced it has invested in the teenager’s company, making Shubham the world’s youngest tech entrepreneur to receive venture capital funding.

“It was curiosity,” explained Shubham, now 13 and an eighth-grader at Champion School in San Jose. “I’m always thinking up something. If you think it can be done, then it can probably be done.”

What started as a home-built Lego project for a science fair has morphed into a family-run startup, with mom Malini Banerjee the president and CEO, and dad Neil Banerjee on the board of directors and also serving as Shubham’s chauffeur and chaperone to press events, interviews and business meetings. The seed funding from Intel will allow the Santa Clara family to hire engineers and product designers, allowing Shubham to return his focus to school and easing the financial burden on the Banerjee family; Neil was contemplating dipping into his 401(k) before Intel made its offer. Intel declined to disclose the amount.

“It’s a classic Silicon Valley story, isn’t it?” said Neil Banerjee, who works as director of software operations for Intel. “Everyone else started in a garage, but (Shubham) started at the kitchen table.”

The investment also earns Shubham a place in history. He is two years younger than British entrepreneur Nick D’Aloisio, who was previously the world’s youngest VC-backed tech entrepreneur when he received an investment for his startup Summly, a news reading app, in 2011, according to business groups and media organizations that track venture investments. Yahoo later bought Summly for a reported $30 million.

Braigo includes software that Shubham created using Intel’s new Edison chip — an inexpensive development platform to power wearable devices, prototypes by early startups and other gadgets built by hobbyists — and a printer that uses various motors and impression tools. Shubham published the code for the software open-source on the web, so other developers can use it, but the family has a patent pending for the printer. Intel engineers, including his dad, helped Shubham build the prototype, which uses spare parts from Fry’s Electronics.

Organizations for those with visual impairment welcome the prospect of an affordable Braille printer, which they say could give people who are blind better access to literature and news and improve Braille literacy rates, which hover at about 8.5 percent among the 60,000 schoolchildren in the country who are blind, according to the American Printing House for the Blind.

“There is absolutely a need,” said Gary Mudd, spokesman for the Printing House for the Blind. “In a business situation, that equipment is purchased by the company that employs you. People who want their own, though, just get to pay for it. Being blind is sometimes very expensive.”

Braille printers start at about $2,000 for personal use and go up to at least $10,000 for schools and businesses. Braigo plans to sell its printer for around $350.

“We had no idea that someone could reinvent a Braille printer and bring the cost down by an order of magnitude,” said Mike Bell, Intel vice president and general manager of the company’s New Devices Group. “We think this has big potential to help a lot of people.”

Because Braigo uses Intel technology, it is an obvious investment for the firm’s venture fund. Possibly the biggest challenge facing Braigo is whether it can get enough customers. The National Federation of the Blind estimates that less than 10 percent of those who are legally blind can read Braille. And with more advanced technology available, including electronic Braille screens and text-to-speech functions on smartphones, some experts expect the demand for Braille printers will drop.

“The number of potential sales are quite limited because there aren’t that many people who read Braille,” said Ike Presley, national project manager for the American Foundation for the Blind. “We don’t know what the demand will be for hard copy Braille five to 10 years from now.”

In five to 10 years, Shubham will be in college, with Braigo perhaps a distant memory. But whether or not the company survives, the experience is almost certainly something his parents will long hold onto.

“He would stay up until 2 a.m., and I would be like, ‘Give it up Shubham, just give it up,” said Malini Banerjee. “He would keep building and breaking things and I would get so discouraged, asking, ‘Why is he wasting his time?’ But now I tell every mom, ‘Believe in your child.'”

Read more stories like this one. Sign up for Disability Scoop's free email newsletter to get the latest developmental disability news sent straight to your inbox.